BURRILLVILLE – Like many inland towns, Burrillville’s bouts with flooding are often small and occur infrequently. Sometimes, you’ll find a makeshift pond on Harrisville Main Street or trickles of water in your basement, but severe cases rarely affect residents, according to Burrillville Building and Zoning official Joe Raymond.

“Most of the flooding issues that we have are very, very specific to particular areas and they haven’t really become much of an issue,” Raymond explained, citing his 25 years as a public servant for the town.

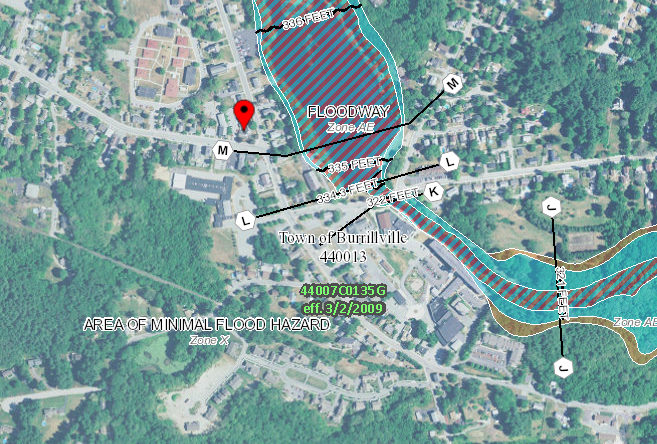

The risk is so small that only 45 properties in Burrillville have flood insurance, he added. Of those 45, it’s unknown how many lie in A-zones – areas with at least 1 percent chance of flooding in any given year – and are required to have insurance, as mandated by the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

These classifications are determined by FEMA and used for their flood mapping service, a standard resource for assessing flood risks across the country and determining flood insurance rates. However, the accuracy of these maps is questionable according to experts like Teresa Crean of the University of Rhode Island’s Coastal Resources Center.

From her own experiences working with Stormtools, an online flood mapper exclusively for the coastline of Rhode Island, she’s seen the discrepancies between FEMA maps and other flood tools that use current models.

“FEMA still owns the roost in terms of regulations,” said Crean, but she recommends property owners to look into other storm tools to help understand their flood risk. While Stormtools doesn’t cover inland towns, she pointed to Flood Factor. The flood mapper allows homeowners to see their property’s flood risk as calculated by the site’s flood model. The tool, created by New York-based non-profit First Street Foundation, takes into account current flooding data and climate change factors such as increased rainfall, both of which aren’t present in FEMA’s maps.

According to Flood Factor, 763 of the nearly 5,000 estimated properties in Burrillville – compiled from data for the town’s villages – are in danger of flooding. A majority of those properties are deemed to be at a major to extreme risk. An additional 30 properties in the next 30 years will become at risk according to the site’s model.

Flood Factor has made national headlines for its robust look at flooding across the country, but the group admits there are caveats to their creation.

According to a New York Times article, “in some areas, including small municipalities, the model may overestimate flood risk because it doesn’t capture every local flood-protection measure, such as pumps or catchment basins.”

Raymond also believes these types of mapping tools, including FEMA’s, can overestimate flood risk because of their lack of understanding of the area.

“Anything that looks like a house, they just put a little rectangle around it,” he says. “You go to the site later, you find out it’s an old abandoned box truck or something like that and now it’s a structure.”

Some properties, like those at Slatersville Reservoir, get lumped into an A-zone despite their high elevations over the reservoir. Others have a portion of their property deemed at-risk, but their home lies outside the floodplain. In instances like these, Raymond recommends residents to write a Letter of Map Amendment. LOMA’s allow property owners to prove they’re at low risk of flooding and remedies faulty FEMA mapping. If a request is approved, your property will be cleared until new developments occur in your area, i.e., a newly built dam.

However, threats of flooding go beyond those in the A-zones. In nearby Smithfield, Sewer Authority Supt. Kevin Cleary deals with some aspect of flooding almost daily. One of his duties is to ensure new developments, even those outside of floodplains, won’t cause flooding problems for the town. This includes enforcing the Smithfield’s zero increase in runoff policy.

“Every building permit that gets issued for new construction receives a review to mitigate the impacts associated with ground cover changes,” Cleary said. “That’s an important thing that I think a lot of communities might miss.”

If gone unchecked – as it has historically – runoff that was once absorbed into the ground can turn into small, “nuisance” floods as Mike Gerel, Program Director of the Narragansett Bay Estuary Program, likes to describe it. Runoff can also make its way into local waterways, spreading pollutants – metals, sediment, bacteria, etc. – along Narragansett Bay’s watershed.

“We’re already seeing significant increases in flooding in inland areas,” said Gerel, stressing the impact climate change is having on Rhode Island communities. “The infrastructure that we’ve built over the last 50 years was not built to the standard to hold this capacity.”

Cleary echoed this sentiment when recounting a substantial storm that hit Rhode Island a few weeks ago.

“We picked up three and a half inches of rainstorm in one shot. That’s a rate of two inches per hour,” he said. “That’s more than any system out there is designed to really even handle.”

Improving infrastructure isn’t cheap either. Cleary estimates $50,000 to $60,000 a year is spent minimizing nuisance flood issues. Large scale projects, typically made possible by grants, can cost towns anywhere from a few $100,000 to over a million dollars.

“It is change and people don’t like change. It can add cost and people don’t like things to be more costly, particularly now,” Gerel said. “But I’ve seen communities be able to deal with this.”