NORTH SMITHFIELD – The business that operates and maintains the dams and infrastructure in the Slatersville Reservoir recently installed a new steel dam holding back water at Centennial Park, leading residents at a downstream apartment complex to question the change of scenery.

And the president of the North Smithfield-based company that owns the new structure and surrounding waterways says it was needed to undo damage caused by an unknown party, which included destruction and theft of historic features in place for more than 150 years.

The five dams that operate on the roughly 180-acre reservoir are co-owned by Dudley Development Corporation and Holliston Sand Co., a business that sells industrial sand and stone. According to state records, Dudley, incorporated in 1963, provides support activities for mining, and Paul Baillargeon is the president of both entities.

“It’s a substantial amount of money to maintain them,” Baillargeon told NRI NOW of the dams this week.

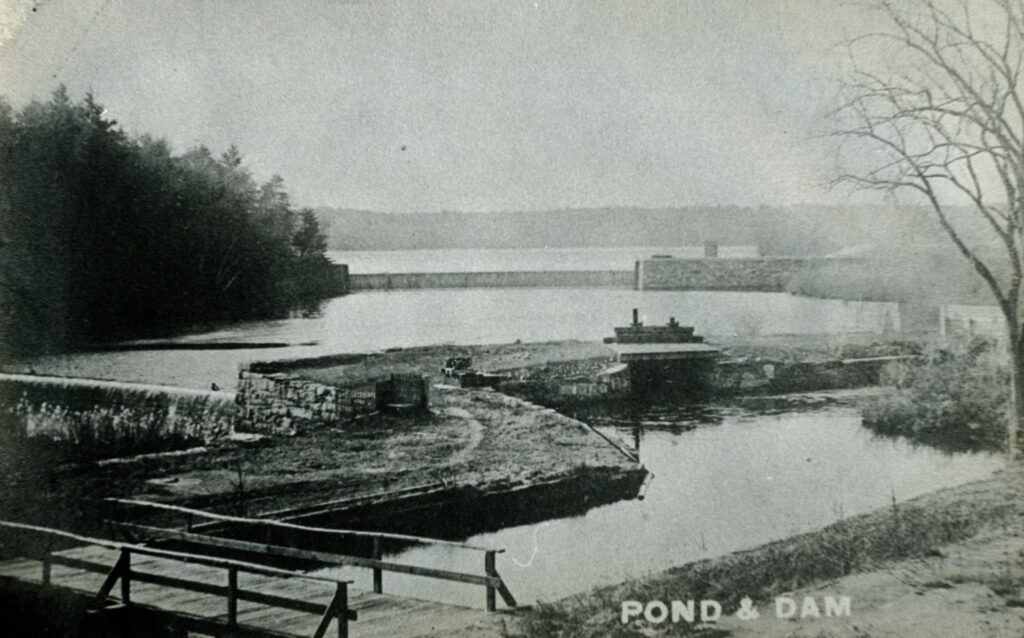

According to Baillargeon, an unknown party destroyed sluice gates on a dam at Centennial Park, a 1.2 acre property situated behind North Smithfield Public Library. The park held two such nineteenth century dams, a manmade canal, a former picker house and the site of the former West Mill.

Just last week, the National Park Service installed signs documenting the significance of the area to the Industrial Revolution touting,”Slater’s Grand Design,” the strategic plan by Samuel Slater to harness the Branch River to power what was once the Slatersville Mill. Today, the refurbished former mill buildings hold luxury apartment housing known as The Residences at Slatersville.

The park was owned and managed by the town library from 1987 until recently in 2021, when library officials said staff was unable to appropriately maintain the grounds, and deeded the lot to the town. The area is one of several sites in Slatersville deemed part of the National Park now known as the Blackstone Valley Historic District due to Slater’s design, and the region’s historic significance as the first planned mill village in America.

But while the short hiking trail and accompanying views of both scenic vistas, and the structures and remnants from that storied history, are open to the public, the water and related infrastructure are privately owned. The river splits into two branches at the park, with the majority of water flowing over a wide dam, and onward toward the nearby Stone Arch Bridge.

The smaller leg has long sent water to the mill, and in modern day Slatersville, has served to retain the historic look and feel of the village, while creating scenic space for those living at The Residences.

Gary Canestrari has lived at the former mill for the past seven years and said that until recently, he’s enjoyed watching the wildlife that’s attracted to the water, from blue heron, to beavers and fish. Not lately, he says.

“It gets low in the summer but not like this,” Canestrari told NRI NOW.

During a visit this week, it was clear that something had changed as other residents of the 200-plus unit apartment complex stared at what is now a stagnant, swampy pond where water once flowed.

Upstream, a new steel dam holds it back, an installation Baillargeon says was deemed necessary to ensure the safety of the second, larger dam.

According to Baillargeon, “out of the blue someone went in and destroyed the sluice gates,” at the smaller dam.

“To the best of our knowledge it was done by a contractor,” he said.

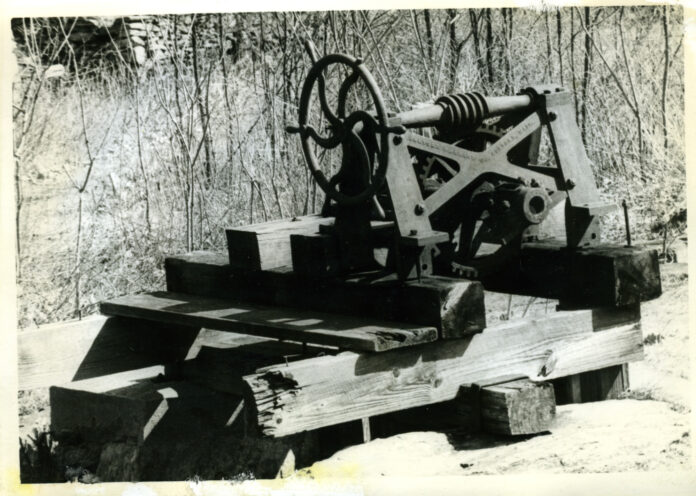

Around the same time, a cast iron wheel, once used to operated the dam – and featured prominently on signs recently installed by NPS – went missing.

“They stole it,” said Baillargeon.

The president said the business had to hire engineers to assess the damage, and was told the larger structure wasn’t getting enough water following the unauthorized alterations to the area. Repairs required help from underwater divers to install the new steel structure and restore flow to the larger dam.

“It could not continue or you would have had a dam failure,” he said. “Stones that have been there since the 1800s were sitting at the bottom of the channel.”

“We spent tens of thousands of dollars to repair what was done,” said Baillargeon.

Christian de Rezendes, a director who has spent the last decade documenting village history for a series on Rhode Island PBS said he had noticed changes to the park, but believed that the wheel was in storage.

“That iron wheel was very, very heavy,” said de Rezendes.

“I don’t know how they did it,” said Baillagereon of the structure’s removal.

Mill residents, meanwhile, received no notice of the change, leading Canestrari to contact the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management. In a letter, Canestrari notes the water diversion, “has resulted in a significant reduction of water flow, leaving the waterfall and the river, along with their diverse wildlife, deprived of the essential water resources necessary for their survival.”

“The Branch River and its associated waterfall have long been cherished natural landmarks within our community, providing not only aesthetic beauty but also serving as vital habitats for various flora and fauna,” he wrote. “The uninterrupted flow of water has sustained an ecosystem teeming with life, offering a haven for countless species, including indigenous fish, amphibians, reptiles, and birds.”

“Recent observations indicate a distressing decline in the water levels of the Branch River, which is especially noticeable at the waterfall site,” Canestrari notes. “The decrease in water flow has had a profound impact on the ecosystem, resulting in adverse consequences for the wildlife that relies on the river for sustenance and shelter.”

Gail Berlinghof, a member of the town’s zoning and water advisory boards, has also been looking into the issue.

“They’re not getting the correct water flow now,” she said this week. “It’s very serious.”

Baillagereon said that if the new structure had decreased water to the area, “it’s blocked at the same level as it was originally designed to.”

No one seemed sure of the historic levels of flow, but de Rezendes noted that the mill area was filmed for what is now the first shot in the first episode of Slatersville, America’s First Mill Village in 1993, and at the time, the water was moving.

“It is very alarming,” he said of the current water level.

Canestrari said he received responses from RI DEM Deputy Administrator Chuck Horbert and Office of Water Resources Administrator Eric Beck, and both were shocked to hear of the change.

“You can’t just shut water off,” Canestrari said. “It’s terrible. Even (Horbert) said it.”

But Baillagereon says he worked with RIDEM to devise the emergency repair plan and restore water to the main dam, on a project that did not require a permit.

“DEM was fully apprised of what was going on,” he said. “They were fully aware. We had to take action to get it fixed.”

Asked this week about the situation, RI DEM spokesman Evan LaCross said DEM’s Office of Water Resources inspected the location on Wednesday, July 5, resulting in an ongoing investigation by the agency’s Office of Compliance and Inspection.

Baillargeon said the office may have noted the lack of permit, and said that he worked with officials at RIDEM who have since left the agency.

“We comply with all the state and federal regulations, and we’ve had no violations in 40 years,” he said.

Regarding the missing wheel, Baillagereon said the business has not filed a police report, but intends to pursue the issue now that the emergency situation has been addressed.

“We’re going to try to do the best we can to find out who’s responsible,” he said. “You get aggravated.”

He notes that his business’s responsibility is to keep water flowing over the larger dam which, if not maintained properly, would have the potential to cause far more damage.

“There’s no obligation of Dudley to provide water to that sluiceway,” he said. “Our obligation is to keep the water flowing as it was designed to, over the dam.”

He noted there may be another solution for the former mill, such as diverting water from the larger side, but it will cost money his company isn’t prepared to spend amid other costly and ongoing maintenance of the reservoir infrastructure.

“We can’t walk away,” he said. “We’ve got the responsibility.”

I’m not sure that putting your nose where it doesn’t belong is an appropriately response, when vandalism, removal and stealing historical property has been identified. This article demands answers from Mr. Baillargeon, DEM and our Town Officials, including the NSHA. Mr. Baillargeon notes vandalism and repair by a contractor. Exactly who might that contractor be?

Diverting a waterway without approval and necessary permits is egregious and should be dealt with as such…Mr. Baillargeon notes that he worked with retirees from DEM, but there appear to be no records? Mr. Baillargeon may own the damns, but does he own the water?

I have previously noted concerns about the groundwater aquifer at NSHS and the installation of solar canopies, but note that at a recent SC meeting this is going out to bid! The same holds true for water in the area of MST. In this town it really is like “wack a mole.”

There seems to be much more to this story and I hope that follow-up will occur. I do feel that there is a complete lack of critical regard for water issues in this community and thank Mr. Canestrari for bringing this issue to light.

This is a great catch 22! If the owners would have neglected this they would be taken to court! Now that they have done something to prevent a problem they will soon be in court. The article claims they have NO OBLIGATION to do anything! This is all about people putting their NOSE WHERE it DON’T BELONG !